November 12, 2020

For Wisconsin’s economy to work for everyone, we need a tax system that takes an active role in undoing the legacy of racial discrimination that makes it difficult for many families of color to thrive. With targeted reforms, state and local tax policies can expand opportunity and ensure that public resources are invested in a way that broadly benefits everyone.

Right now, Wisconsin’s tax system isn’t living up to its potential to be a powerful tool in promoting equitable opportunity. Our slanted tax system isn’t the only reason for Wisconsin’s enormous racial disparities, but it contributes by saddling residents of color with an unfair economic burden that makes it harder to succeed financially.

Our state and local tax code does not mention race. And yet it systematically demands that people of color pay a higher share of their income in taxes than white residents, showing that policies don’t have to explicitly mention race in order to have racially discriminatory consequences. The myth that the tax code “doesn’t see color” allows us to dismiss the role that tax policies have played in creating Wisconsin’s enormous racial disparities.

The racial preferences that are baked into Wisconsin’s property tax code take the form of very large property tax credits that give bigger tax breaks to homeowners than to renters, even though both groups pay property taxes. At the state level, Wisconsin spends more than a billion dollars a year on these tax credits. Homeowners pay property tax directly, while renters pay property tax as a portion of their rent, when landlords set the rent at a level they need to cover all expenses, including expenses like the mortgage, maintenance, and property taxes, the costs of which are then passed to the renters.

Because the state provides larger financial benefits to homeowners than to renters – and because White residents are more likely to own their own home – White residents get a larger share of property tax credits that give preference to homeowners, and therefore pay lower property taxes than they otherwise would. Residents of color have to make up the difference.

Historic and current practices have set up roadblocks to homeownership for residents of color, lowering their homeownership rate and resulting in larger tax cuts being directed to white homeowners. Restrictive housing agreements long prohibited residents of color from living in certain areas of the Milwaukee suburbs and other parts of Wisconsin, limiting the areas in which residents of color could live and work. Federal lending practices specifically discouraged banks from issuing mortgages in neighborhoods with a high percentage of residents of color, starving those areas of investment and making it harder for residents of color to live in their own home regardless of their own individual credit worthiness.

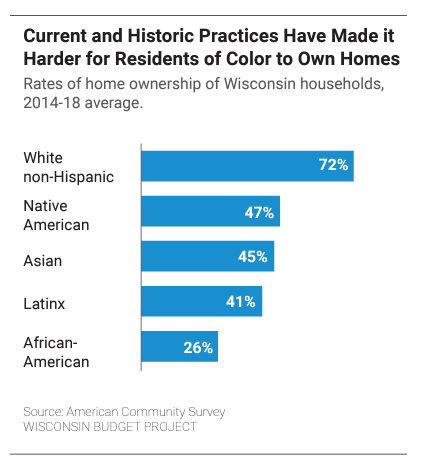

The results of these discriminatory actions can be seen in the different rates of homeownership by race in Wisconsin. White residents of the state are nearly three times as likely to own their own home as African-American residents. A large majority of White residents (72%) own their own homes, something that is true of less than a third of African-American (26%) residents, and less than half of Latinx (41%), Asian (45%), and Native American (47%) residents.

The exclusion of so many people of color from home ownership prevents them from benefiting from two of the largest federal and state tax breaks—the income tax deductions for property taxes and mortgage interest. The systemic bias in the tax code against people of color can also be seen in Wisconsin’s two largest property tax credits, the School Levy Credit and the Lottery Credit, which together reduced Wisconsin property taxes by $1.2 billion in 2019. Because of policy choices made by Wisconsin lawmakers, they didn’t reduce property taxes equitably for people of different races.

Both the School Levy Credit and the Lottery Credit exclude renters from directly receiving the credit. Renters can benefit indirectly from the School Levy Credit, which reduces property taxes for all owners of property located in Wisconsin, including landlords who rent out residential property. That means that some portion—but only a portion—of the School Levy Credit flows through to renters, to the extent that landlords reduce the rent they charge to take lower costs into account. The Lottery Credit doesn’t provide any benefit to renters at all, as it only reduces property taxes for homeowners on their primary residence.

Even though renters pay property taxes, Wisconsin lawmakers have created a system of property tax credits that predominantly benefit homeowners and largely blocks renters from directly benefiting. However, one property tax credit—the Homestead Credit—reduces property taxes more equitably by benefiting both homeowners and renters. Unfortunately, policy choices made by state lawmakers have sharply reduced the amount of relief provided by the Homestead Credit.

To build a tax system that provides an equal playing field for all Wisconsin residents, state lawmakers should direct additional resources to the Homestead Credit while cutting back on credits that favor homeowners. The Reimagine Wisconsin agenda, a set of key strategies for moving Wisconsin forward on a path to an equity economy, has additional recommendations for restructuring our tax system.

There are some bright spots in Wisconsin’s tax code in the form of policies that counteract the overall trend of exploitation of people of color and people with low incomes. State lawmakers can build on and expand these policies to make sure that Wisconsin’s tax system is equitable. Otherwise, lawmakers will continue to support a system that thwarts economic opportunity for people with low incomes and people of color by forcing them to pay more than their fair share.