March 18, 2020, by Tamarine Cornelius

Communities across the country are scrambling to mitigate the harm done by the coronavirus. But local governments in Wisconsin are finding that the state government has tied their hands by blocking several steps that communities could take to protect the health and well-being of their residents.

One of the most damaging constraints was taken by Wisconsin legislators several years ago: blocking local communities from passing ordinances requiring paid sick leave. Even during normal times, common sense tells us that workers who are sick need to be able to stay home from work so that they don’t pass their illness on to other people.

And yet when Milwaukee became one of the first cities in the nation to require that workers have access to paid sick leave, Governor Walker and the legislature reversed their decision and prohibited any other local government in the state from following Milwaukee’s example.

The result is that far too few workers in Wisconsin have paid sick leave. That means that workers face a terrible choice between (a) going to work sick or (b) staying home and risking losing their wages or even their job. That loss of wages could mean not being able to afford putting food on their table for their families, or paying their rent.

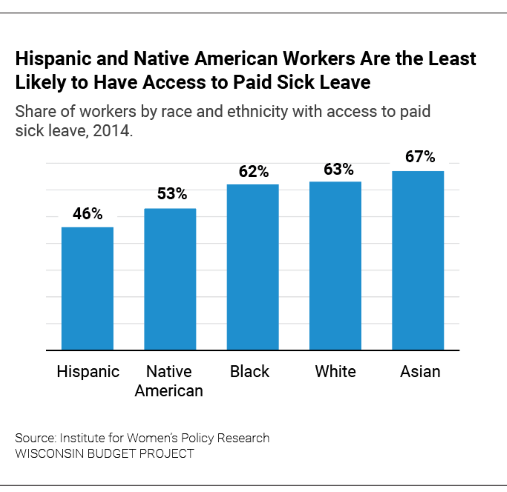

The lack of paid sick leave hits workers of color the hardest. Only 46% of Hispanic workers and 53% of Native American workers have access to paid sick leave, significantly lower than the 63% of white workers with paid sick leave, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

In addition to blocking local ordinances requiring paid sick leave, state statutes block communities from putting a temporary hold on evictions during a time of crisis. During the outbreak, many residents are losing their incomes and can’t afford to pay their rent. Officials in cities like Denver, Seattle, San Francisco, and San Antonio have halted all evictions to mitigate the economic damage inflicted by the pandemic.

Mayors in Wisconsin, however, don’t have the option to put a moratorium on evictions. Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway noted that she would suspend evictions “in a heartbeat,” but is specifically prevented from doing so by state law. (The courts are closed right now so evictions can’t proceed, but that doesn’t mean landlords can’t file.)

Like the ban on requiring paid sick leave, the prohibition on halting evictions is more likely to harm residents of color than white residents. Some research has shown that eviction rates among black and Latinx adults are almost seven times higher than for white residents. Residents of color are more likely to pay a higher share of their income in housing costs, due to racial discrimination in the employment market that reduces their income, making it difficult for them to afford rent even in good economic times.

To address the economic harm done by this pandemic, and the disproportionate harm felt by communities of color, we need coordinated action on all levels of government. But in Wisconsin, a state that used to pride itself in its level of local control, the state legislature has hamstrung local governments, making it harder for them to protect workers and help families. The effects of those limitations were bad enough before the pandemic. Now the damage is intensified, with the final cost still unknown.