June 28, 2016

A new tax credit that allows manufacturers and some other businesses to pay next to nothing in income taxes has ballooned far beyond original cost estimates and has done little to promote job creation.

The Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit, which lawmakers passed in 2011, nearly wipes out income taxes for manufacturers and agricultural producers — at a very steep price. The tax credit reduces state income tax revenues by $284 million a year in fiscal year 2017 and in subsequent years. Most of the credit goes towards reducing income taxes for millionaires, with some tax filers with incomes of over $1 million receiving tax cuts of more than $100,000. In contrast, individuals with moderate or low incomes receive next to nothing in terms of a tax cut.

Companies are eligible to receive the credit regardless of whether they create new jobs. Even businesses that lay off workers, send jobs overseas, and close factories are eligible to receive the credit. Given the lack of any requirements to create jobs, it is not surprising that there isn’t much in the way of evidence the credit has encouraged manufacturers to hire new workers. A review of employment figures shows that there has not been an increase in the rate of growth of manufacturing jobs since the credit has been in place.

At the same time that the Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit (MAC) is giving very significant tax breaks to the very wealthiest individuals, lawmakers are cutting back on investments in Wisconsin’s education system and communities. In fact, Wisconsin’s cuts in state support for public schools and higher education system are among the largest in the country. By approving the MAC, lawmakers are giving a higher priority to giving tax cuts for the best-off than avoiding additional cuts to Wisconsin’s schools and universities.

Costly Tax Credit Almost Exclusively Benefits Wealthy

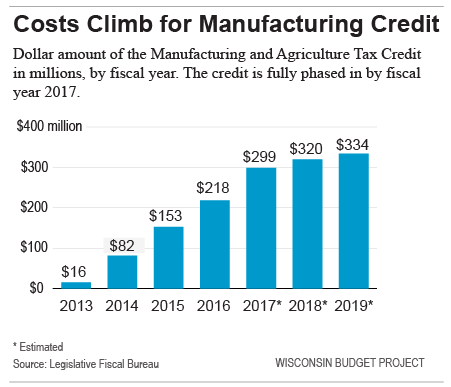

The Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit is estimated to reduce state tax collections by $284 million annually, once the credit is fully phased in starting in fiscal year 2017.

When lawmakers included the MAC in the 2011-13 budget, they set the credit to phase in over several years. That decision means the cost of the credit started small — $15 million in 2013 — and grew in subsequent years, reaching its full cost in fiscal year 2017.

The credit reduces the amount of income taxes, either corporate or individual, that would otherwise be owed on income from manufacturing and agricultural activities. In many cases, the credit will reduce the income taxes on that income to zero, wiping out any tax liability.

The MAC is equal to a specified portion of qualified income earned from property assessed for manufacturing or agricultural purposes. The credit percentage was phased in over four tax years, and is set at 7.5% for tax year 2016 and subsequent years.

Starting in 2016, the MAC is set at a level (7.5%) that is higher than all but the top bracket for individual income tax rates (7.65%), and nearly equal to the corporate income tax rate (7.9%). That means the credit will wipe out all tax liability on qualifying income for many individuals, and will drastically reduce tax liability for corporations and those individuals who will still have to pay some taxes. The credit cannot be used to offset the tax on other sources of income and is not refundable, but tax filers can carry forward unused credits for 15 years.

While both manufacturers and agricultural producers can receive the credit, most of the tax cut goes to manufacturers. In the past, about $5 out of every $6 of the credit has cut taxes for manufacturing businesses. Assuming past trends hold, that means manufacturers would receive an estimated tax cut of $237 million tax cut in fiscal year 2017, with the remaining $47 million going to agricultural producers. The actual share of the credit that benefits manufacturers varies from one year to the next, based on the profitability of businesses and other economic trends.

A boon for the wealthy

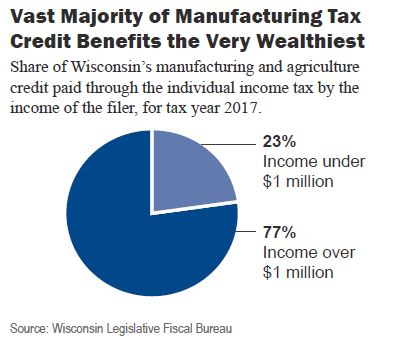

The MAC gives extremely large tax cuts to the very highest earners, with very little of the credit going to tax filers with moderate or low incomes.

Tax filers with incomes of $1 million and higher, who made up just 0.2% of filers, receive an estimated 78% of the 2016 tax cut that is distributed through the individual income tax. Filers with incomes of between $300,000 and $1 million, who make up 1.0% of all filers, receive 15% of the tax cut. The remaining 98.8% of tax filers, who earn less than $300,000, receive 7% of the tax cut.

Information on the income of the filers who receive the credit is available for the portion of the credit distributed through the individual income tax, but not the corporate income tax. Most of the credit value — about 70% — is distributed through the individual income tax, meaning that comparisons of distributions by filers of different income levels for the individual income portion would likely hold true for the full amount of the credit. Figures describing the distribution of the MAC are taken from Wisconsin Department of Revenue estimates, and are based on Wisconsin Adjusted Gross Income.

Tax filers with the very highest incomes receive much bigger tax cuts from the MAC on average than do filers with lower incomes. Tax filers who had incomes of $1 million and higher receive an average MAC credit of $27,632, according to estimates for tax year 2016. That amount includes filers who receive credit amounts of zero. Filers with incomes between $300,000 and $1 million receive an average tax cut of $958 in 2016. Tax filers with incomes of under $300,000, a group that makes up nearly 99% of tax filers, receive an average tax cut of $5.

In 2016, an estimated 10,000 tax filers will claim the MAC, and a disproportionately large number of those claimants have very high incomes. Of tax filers with incomes of $1 million and greater, 1 out of 4 filers receive the credit. That drops to 1 out of every 18 filers receiving the credit for those with incomes between $300,000 and $1 million. For tax filers with incomes of under $300,000, only 1 out of every 430 filers receive the credit.

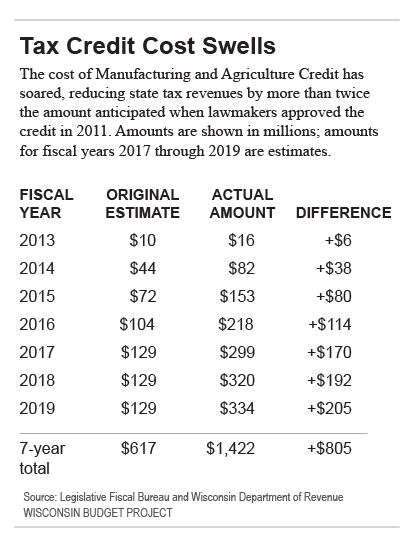

Unexpectedly high cost takes lawmakers by surprise

The credit has cost much more than originally anticipated. When lawmakers passed the tax break in 2011, the credit was estimated to reduce income tax collections by $129 million in fiscal year 2017, when the credit is fully phased in. But an updated estimate by Wisconsin’s Department of Revenue shows the credit is now expected to swell to $284 million in fiscal year 2017. That’s an increase of $155 million, or 121% above the size of the tax cut that lawmakers thought they were passing when they put the tax cut in the 2011-13 budget bill.

Part of the discrepancy between the original estimated cost and later estimations stems from the difficulty of predicting the degree to which credits like this one, which are based on business profits, will reduce tax revenues. In a February 2015 letter, the Legislative Fiscal Bureau explained why the actual costs of the MAC differed so significantly from the estimates: “[B]usiness profits fluctuate considerably from year-to-year and are difficult to forecast accurately…Because of this uncertainty, the fiscal impacts of tax provisions that are based on business profits are inherently difficult to forecast reliably and will exhibit similar annual fluctuations.” The memo also cited limitations in the type of information that was available to use in forecasting the cost of the credit as another reason the credit has reduced tax revenues by much more than originally anticipated.

Regardless of the reason, MAC has turned out to be more than twice as large as lawmakers originally intended. That means the legislature could cut the amount of the credit in half and still give manufacturers an income tax cut in line with what was originally intended.

An Ineffective Tool for Encouraging Job Growth

The Manufacturing and Agriculture Tax Credit carries significant costs, and in order for the credit to be considered effective, we should see strong evidence that the credit has boosted the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin. But there is little evidence the credit has had any effect on the state’s manufacturing sector.

There is no doubt that manufacturing jobs are important for Wisconsin’s families. Wisconsin’s manufacturing industries employ far fewer people than in decades past, but manufacturing jobs are still an integral part of Wisconsin’s economy. More than 450,000 Wisconsin workers work in manufacturing, making up nearly 1 out of every 5 private sector jobs. Only one state — Indiana — has a higher share of workers in manufacturing. Manufacturing jobs pay better than jobs in other sectors, on average: in Wisconsin, the average manufacturing job pays $55,400, compared to $45,200 for private sector jobs as a whole.

Despite the importance of manufacturing jobs to Wisconsin families, there is no requirement that businesses add new jobs in order to receive the credit. On the contrary, even companies that lay off workers, send jobs overseas, and close factories are eligible to claim the credit.

There are many examples of manufacturers that are closing factories or laying off workers and which still may be eligible to claim the credit. Once a business ceases all manufacturing activities in Wisconsin, it is no longer eligible for the credit, but businesses may still claim the credit if they close one of several plants in Wisconsin, or as they are in the process of phasing out manufacturing operations completely. Information on which companies actually receive the credit is not publicly available, but likely recipients include:

- Kraft Heinz Foods Company, which gave notice it will eliminate more than 1,000 jobs in Madison and close the Oscar Mayer plant there;

- Graphic Packaging International, which gave notice it will close its paper converting plant in Menasha and lay off 228 workers;

- Manitowoc Cranes, which gave notice to close its Port Washington factory and put 80 workers out of work; and

- Chart Chemical and Energy, which gave notice for laying off 104 workers at its LaCrosse plant at the end of 2015.

Little effect seen on job growth

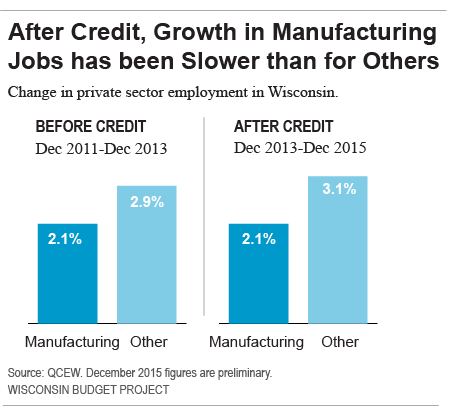

Wisconsin taxpayers have little to show for the lost tax revenue caused by the Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit. Wisconsin has added manufacturing jobs at exactly the same pace in the period before the credit as in the period after the credit, a sign that the credit is likely not spurring the growth of manufacturing jobs. Both before and after the credit became available, the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin grew more slowly than the number of jobs in other industries.

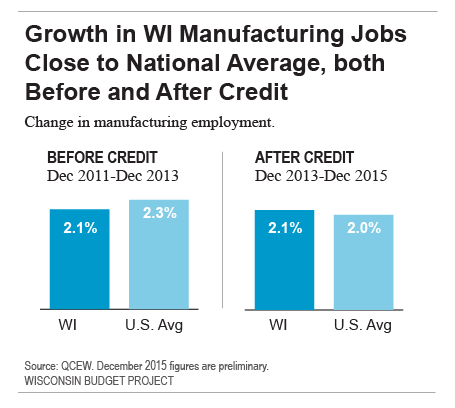

Between December 2011 and December 2013, before the MAC was implemented, the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin grew by 2.1%. That is the same rate of growth as in the two year period after manufacturers received the large tax break from the MAC. It is hard to know how the number of manufacturing jobs would have changed in the absence of a large tax break for manufacturers, but the lack of an increase in the rate of growth points to the likelihood that the credit has not affected manufacturing employment in Wisconsin.

If the MAC helped strengthen the state’s manufacturing industry, it would be reasonable to expect that the number of manufacturing jobs would grow more quickly than the number of jobs in sectors that did not receive the credit. However, that is not the case. In a two-year period after the tax credit was implemented, the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin grew considerably more slowly than did the number of non-manufacturing jobs: 2.1% growth for manufacturing jobs, compared to 3.1% growth in other private sector jobs between December 2013 and December 2015. Before the credit, the number of manufacturing jobs also grew more slowly than other private-sector jobs.

Before and after credit, Wisconsin growth in manufacturing about average

If the Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit helped Wisconsin’s manufacturing industry to expand, we might expect that the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin would grow significantly faster than the national average in the period after the credit took effect. That did not happen, again demonstrating that the credit is doing little to expand Wisconsin’s manufacturing industry.

Both before and after the credit took effect, Wisconsin added manufacturing jobs at about the same rate as the national average. Between December 2011 and December 2013, the two years before the credit, Wisconsin manufacturing jobs grew by 2.1%, close to the national average of 2.3%. After the credit was implemented, the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin grew by 2.1% between December 213 and December 2015, nearly identical to the national average of 2.0%. Wisconsin ranked exactly in the middle — 25th among the states — in the rate of job growth in manufacturing in the period after the credit was implemented.

These employment figures are taken from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), which includes information from a large number of employers and is considered the gold standard for information about employment levels. Figures from the QCEW must be compared to figures from the same month in a previous year in order to be valid. This analysis uses the most recent QCEW employment figures available, which are preliminary figures for December 2015.

Another, more up-to-date but less reliable data source shows a more mixed picture on comparisons between Wisconsin and the U.S. The Current Employment Statistics, published monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, show that the number of manufacturing jobs in Wisconsin grew slightly slower than the national average for part of the time in the period after the credit was passed, and more quickly than the national average at other times.

Taken together, the information from the two data sources points to the likelihood that Wisconsin’s manufacturing sector is doing about as well as the national average in adding jobs. Nearly wiping out taxes on income earned from manufacturing has not caused Wisconsin to add jobs faster than the national rate, and has reduced the amount of tax revenue Wisconsin can invest in other priorities, like improving schools, communities, and roads.

Misplaced Priorities, with a High Price Tag

Effective support for Wisconsin’s businesses could increase the number of good-paying jobs in Wisconsin and help Wisconsin remain a manufacturing leader. But the Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit is set up in a way that allows individuals and corporations to receive very large tax breaks without creating a single new job.

If state lawmakers want to take a more effective approach to helping Wisconsin businesses thrive and hire more workers, they should consider taking the $284 million in tax revenue that will be lost annually to the credit, and instead invest those resources to improve Wisconsin’s workforce and infrastructure. For the same amount of money as the state is losing in tax revenue to the Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit, Wisconsin could:

- Waive all tuition and fees for the more than 70,000 students statewide attending Wisconsin’s technical colleges. This move would make it more affordable for workers to get the skills they need and would make it easier for employers to find qualified employees.

- Rehabilitate and improve more than 600 miles of state highways. Seventy-one percent of Wisconsin’s roads are in poor or mediocre condition, according to the American Society of Civil Engineers, and only two states have a higher share of roads in unsatisfactory condition than does Wisconsin. A reliable transportation network makes it easier for businesses to bring in the supplies they need and get their products to market.

- Pay the full cost of adding 4,000 teachers to Wisconsin’s K-12 classrooms. The number of teachers in Wisconsin has dropped in recent years, resulting in crowded classrooms and making it harder for students to learn. Adding teachers would help make sure that Wisconsin students graduating from high school have the solid foundation they need to go on to get more advanced degrees or enter the workforce.

These alternatives would have the added advantage of improving the state’s workforce and infrastructure for all businesses. As it stands, the MAC gives manufacturers and agricultural producers a tax advantage over similarly situated businesses in other sectors of the state’s economy, leading some lawmakers to criticize the MAC as an example of the state “picking winners and losers.”

The manufacturing sector employs a large share of Wisconsin workers and plays an important role in the state’s economy. But given the growth in overseas manufacturing and the increased mechanization of manufacturing processes and plants, the manufacturing industry in Wisconsin and other states is unlikely to reach the employment levels of a decade ago. Rather than investing a great deal of lost tax revenue in an industry that is unlikely to have serious growth potential, Wisconsin should focus on boosting employment and wages across all sectors.

The Manufacturing and Agriculture Credit is part of a recent legislative agenda of cutting taxes and reducing public investments in communities — an agenda that has not succeeded in spurring job creation. Wisconsin continues to add jobs more slowly than the national average: in 2015, the number of private sector jobs in Wisconsin grew by 1.3%, compared to 2.1% nationally. That means for every 100 jobs added in other states, Wisconsin only added 63. Wisconsin ranked 36th among the states in the rate of private sector job growth in 2015, behind the neighboring states of Minnesota, Michigan, and Illinois.

The focus on cutting taxes has not boosted job creation, but it has reduced the resources available to invest in Wisconsin’s public schools, workforce, and communities. Wisconsin’s cuts in state support to public schools are among the largest in the country, and Wisconsin’s cut to higher education between 2015 and 2016 was the second-largest in the country, measured in percent change in state spending per student. These cuts will make it harder for manufacturers and other businesses to hire the skilled workers they need.

Tamarine Cornelius